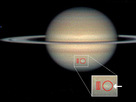

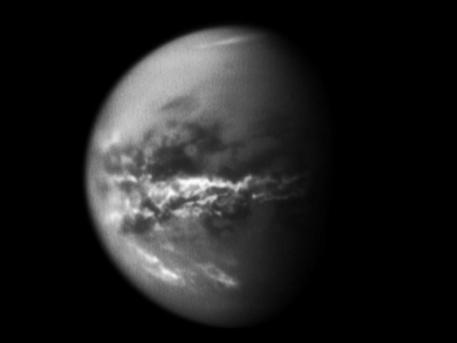

Equatorial Titan Clouds

Cassini Sees Seasonal Rains Transform Titan's Surface

© NASA/JPL/SSI

|

NASA's Cassini spacecraft chronicles the change of seasons as it captures clouds concentrated near the equator of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Methane clouds in the troposphere, the lowest part of the atmosphere, appear white here and are mostly near Titan's equator. The darkest areas are surface features that have a low albedo, meaning they do not reflect much light. Cassini observations of clouds like these provide evidence of a seasonal shift of Titan's weather systems to low latitudes following the August 2009 equinox in the Saturnian system. (During equinox, the sun lies directly over the equator. See PIA11667 to learn how the sun's illumination of the Saturnian system changed during the equinox transition to spring in the northern hemispheres and to fall in the southern hemispheres of the planet and its moons.)

"It's amazing to be watching such familiar activity as rainstorms and seasonal changes in weather patterns on a distant, icy satellite," said Elizabeth Turtle, a Cassini imaging team associate at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, Md., and lead author of today's publication. "These observations are helping us to understand how Titan works as a system, as well as similar processes on our own planet."

The Saturn system experienced equinox, when the sun lies directly over a planet's equator and seasons change, in August 2009. (A full Saturn "year" is almost 30 Earth years.) Years of Cassini observations suggest Titan's global atmospheric circulation pattern responds to the changes in solar illumination, influenced by the atmosphere and the surface, as detailed in the Geophysical Research Letters paper. Cassini found the surface temperature responds more rapidly to sunlight changes than does the thick atmosphere. The changing circulation pattern produced clouds in Titan's equatorial region.

Clouds on Titan are formed of methane as part of an Earth-like cycle that uses methane instead of water. On Titan, methane fills lakes on the surface, saturates clouds in the atmosphere, and falls as rain. Though there is evidence that liquids have flowed on the surface at Titan's equator in the past, liquid hydrocarbons, such as methane and ethane, had only been observed on the surface in lakes at polar latitudes. The vast expanses of dunes that dominate Titan's equatorial regions require a predominantly arid climate. Scientists suspected that clouds might appear at Titan's equatorial latitudes as spring in the northern hemisphere progressed. But they were not sure if dry channels previously observed were cut by seasonal rains or remained from an earlier, wetter climate.

An arrow-shaped storm appeared in the equatorial regions on Sept. 27, 2010 -- the equivalent of early April in Titan's "year" -- and a broad band of clouds appeared the next month. As described in the Science paper, over the next few months, Cassini's imaging science subsystem captured short-lived surface changes visible in images of Titan's surface. A 193,000-square-mile (500,000-square-kilometer) region along the southern boundary of Titan's Belet dune field, as well as smaller areas nearby, had become darker. Scientists compared the imaging data to data obtained by other instruments and ruled out other possible causes for surface changes. They concluded this change in brightness is most likely the result of surface wetting by methane rain.

These observations suggest that recent weather on Titan is similar to that over Earth's tropics. In tropical regions, Earth receives its most direct sunlight, creating a band of rising motion and rain clouds that encircle the planet.

"These outbreaks may be the Titan equivalent of what creates Earth's tropical rainforest climates, even though the delayed reaction to the change of seasons and the apparently sudden shift is more reminiscent of Earth's behavior over the tropical oceans than over tropical land areas," said Tony Del Genio of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York, a co-author and a member of the Cassini imaging team.

On Earth, the tropical bands of rain clouds shift slightly with the seasons but are present within the tropics year-round. On Titan, such extensive bands of clouds may only be prevalent in the tropics near the equinoxes and move to much higher latitudes as the planet approaches the solstices. The imaging team intends to watch whether Titan evolves in this fashion as the seasons progress from spring toward northern summer.

"It is patently clear that there is so much more to learn from Cassini about seasonal forcing of a complex surface-atmosphere system like Titan's and, in turn, how it is similar to, or differs from, the Earth's," said Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team lead at the Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colo. "We are eager to see what the rest of Cassini's Solstice Mission will bring."

Source: NASA

Equatorial Titan Clouds

Cassini Sees Seasonal Rains Transform Titan's Surface

© NASA/JPL/SSI

|

NASA's Cassini spacecraft chronicles the change of seasons as it captures clouds concentrated near the equator of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Methane clouds in the troposphere, the lowest part of the atmosphere, appear white here and are mostly near Titan's equator. The darkest areas are surface features that have a low albedo, meaning they do not reflect much light. Cassini observations of clouds like these provide evidence of a seasonal shift of Titan's weather systems to low latitudes following the August 2009 equinox in the Saturnian system. (During equinox, the sun lies directly over the equator. See PIA11667 to learn how the sun's illumination of the Saturnian system changed during the equinox transition to spring in the northern hemispheres and to fall in the southern hemispheres of the planet and its moons.)

"It's amazing to be watching such familiar activity as rainstorms and seasonal changes in weather patterns on a distant, icy satellite," said Elizabeth Turtle, a Cassini imaging team associate at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, Md., and lead author of today's publication. "These observations are helping us to understand how Titan works as a system, as well as similar processes on our own planet."

The Saturn system experienced equinox, when the sun lies directly over a planet's equator and seasons change, in August 2009. (A full Saturn "year" is almost 30 Earth years.) Years of Cassini observations suggest Titan's global atmospheric circulation pattern responds to the changes in solar illumination, influenced by the atmosphere and the surface, as detailed in the Geophysical Research Letters paper. Cassini found the surface temperature responds more rapidly to sunlight changes than does the thick atmosphere. The changing circulation pattern produced clouds in Titan's equatorial region.

Clouds on Titan are formed of methane as part of an Earth-like cycle that uses methane instead of water. On Titan, methane fills lakes on the surface, saturates clouds in the atmosphere, and falls as rain. Though there is evidence that liquids have flowed on the surface at Titan's equator in the past, liquid hydrocarbons, such as methane and ethane, had only been observed on the surface in lakes at polar latitudes. The vast expanses of dunes that dominate Titan's equatorial regions require a predominantly arid climate. Scientists suspected that clouds might appear at Titan's equatorial latitudes as spring in the northern hemisphere progressed. But they were not sure if dry channels previously observed were cut by seasonal rains or remained from an earlier, wetter climate.

An arrow-shaped storm appeared in the equatorial regions on Sept. 27, 2010 -- the equivalent of early April in Titan's "year" -- and a broad band of clouds appeared the next month. As described in the Science paper, over the next few months, Cassini's imaging science subsystem captured short-lived surface changes visible in images of Titan's surface. A 193,000-square-mile (500,000-square-kilometer) region along the southern boundary of Titan's Belet dune field, as well as smaller areas nearby, had become darker. Scientists compared the imaging data to data obtained by other instruments and ruled out other possible causes for surface changes. They concluded this change in brightness is most likely the result of surface wetting by methane rain.

These observations suggest that recent weather on Titan is similar to that over Earth's tropics. In tropical regions, Earth receives its most direct sunlight, creating a band of rising motion and rain clouds that encircle the planet.

"These outbreaks may be the Titan equivalent of what creates Earth's tropical rainforest climates, even though the delayed reaction to the change of seasons and the apparently sudden shift is more reminiscent of Earth's behavior over the tropical oceans than over tropical land areas," said Tony Del Genio of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York, a co-author and a member of the Cassini imaging team.

On Earth, the tropical bands of rain clouds shift slightly with the seasons but are present within the tropics year-round. On Titan, such extensive bands of clouds may only be prevalent in the tropics near the equinoxes and move to much higher latitudes as the planet approaches the solstices. The imaging team intends to watch whether Titan evolves in this fashion as the seasons progress from spring toward northern summer.

"It is patently clear that there is so much more to learn from Cassini about seasonal forcing of a complex surface-atmosphere system like Titan's and, in turn, how it is similar to, or differs from, the Earth's," said Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team lead at the Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colo. "We are eager to see what the rest of Cassini's Solstice Mission will bring."

Source: NASA