The Sun's hot atmosphere explained

Tiny flares creating big heat

The mystery of why temperatures in the solar corona, the sun's outer atmosphere, soar to several million degrees Kelvin (K) - much hotter than temperatures nearer the sun's surface - has puzzled scientists for decades. New observations made with instruments aboard Japan's Hinode satellite reveal the culprit to be nanoflares.

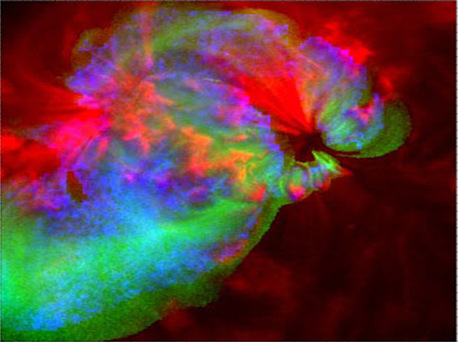

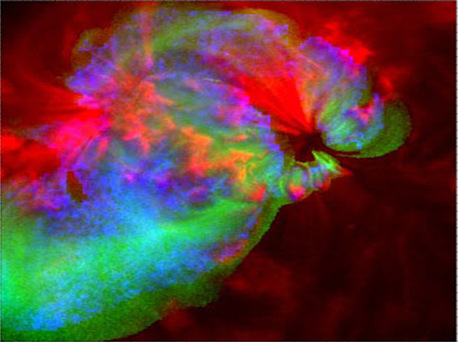

© Reale, et al. (2009)

|

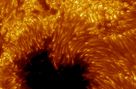

This false-color temperature map shows solar active region AR10923, observed close to center of the sun's disk. Blue regions indicate plasma near 10 million degrees K.

"Why is the sun's corona so darned hot?" asks James Klimchuk, an astrophysicist with NASA. New observations made with instruments aboard Japan's Hinode satellite reveal the culprit to be nanoflares.

Nanoflares are small, sudden bursts of heat and energy. "They occur within tiny strands that are bundled together to form a magnetic tube called a coronal loop," says Klimchuk. Coronal loops are the fundamental building blocks of the thin, translucent gas known as the sun's corona.

Scientists previously thought steady heating explained the corona's million degree temperatures. However, observations showed that coronal loops have much higher density than the steady heating model predicts. Newer models based on nanoflares can explain the observed density. But no direct evidence of the nanoflares existed until now.

"Coronal loops are bundles of unresolved strands that are heated by storms of nanoflares."

Coronal heating is a dynamic process. The brightness of the observed X-ray and ultraviolet emission is strongly dependent on the density of the coronal plasma. Where there's low density, there isn't much brightness. Where there's high density, there's a lot of brightness. The corona is mostly bright at about 1 million degrees K.

Klimchuk and colleagues constructed a theoretical model to explain how plasma evolves within these coronal tubes and what causes temperatures to skyrocket. "We simulate a burst of heating and see how the corona responds," says Klimchuk. "Then we make predictions about how much emission we should see from plasma of different temperatures."

"What we see is 1 million degree K plasma that has received its energy from the heat flowing down from the superhot plasma," says Klimchuk. "For the first time, we have detected this 10 million degree plasma, which can only be produced by the impulsive energy bursts of nanoflares."

The Hinode observations and the scientists' analysis verify that nanoflares are occurring on the sun and that they explain much and perhaps most coronal heating. The observations also confirm "there is some nanoflare activity everywhere" in the sun's active regions, says Klimchuk.

Nanoflares influence satellites and radios

Nanoflares are responsible for changes in the X-ray and ultraviolet (UV) radiation that happen as an active region evolves. X-ray and UV get absorbed by Earth's upper atmosphere, which heats up and expands. Changes in the upper atmosphere can affect the orbits of satellites and space debris by slowing them down, an effect known as "drag." It is important to know the changing orbits so that maneuvers can be made to avoid space collisions. The X-ray and UV also affect the propagation of radio signals and thereby adversely affect communication and navigation systems.

The discovery that nanoflares play an important and perhaps dominant role in coronal heating paves the way to understanding how the sun affects Earth, our place in the universe.

Nanoflares are small, sudden bursts of heat and energy. "They occur within tiny strands that are bundled together to form a magnetic tube called a coronal loop," says Klimchuk. Coronal loops are the fundamental building blocks of the thin, translucent gas known as the sun's corona.

Scientists previously thought steady heating explained the corona's million degree temperatures. However, observations showed that coronal loops have much higher density than the steady heating model predicts. Newer models based on nanoflares can explain the observed density. But no direct evidence of the nanoflares existed until now.

"Coronal loops are bundles of unresolved strands that are heated by storms of nanoflares."

Coronal heating is a dynamic process. The brightness of the observed X-ray and ultraviolet emission is strongly dependent on the density of the coronal plasma. Where there's low density, there isn't much brightness. Where there's high density, there's a lot of brightness. The corona is mostly bright at about 1 million degrees K.

Klimchuk and colleagues constructed a theoretical model to explain how plasma evolves within these coronal tubes and what causes temperatures to skyrocket. "We simulate a burst of heating and see how the corona responds," says Klimchuk. "Then we make predictions about how much emission we should see from plasma of different temperatures."

"What we see is 1 million degree K plasma that has received its energy from the heat flowing down from the superhot plasma," says Klimchuk. "For the first time, we have detected this 10 million degree plasma, which can only be produced by the impulsive energy bursts of nanoflares."

The Hinode observations and the scientists' analysis verify that nanoflares are occurring on the sun and that they explain much and perhaps most coronal heating. The observations also confirm "there is some nanoflare activity everywhere" in the sun's active regions, says Klimchuk.

Nanoflares influence satellites and radios

Nanoflares are responsible for changes in the X-ray and ultraviolet (UV) radiation that happen as an active region evolves. X-ray and UV get absorbed by Earth's upper atmosphere, which heats up and expands. Changes in the upper atmosphere can affect the orbits of satellites and space debris by slowing them down, an effect known as "drag." It is important to know the changing orbits so that maneuvers can be made to avoid space collisions. The X-ray and UV also affect the propagation of radio signals and thereby adversely affect communication and navigation systems.

The discovery that nanoflares play an important and perhaps dominant role in coronal heating paves the way to understanding how the sun affects Earth, our place in the universe.

The Sun's hot atmosphere explained

Tiny flares creating big heat

The mystery of why temperatures in the solar corona, the sun's outer atmosphere, soar to several million degrees Kelvin (K) - much hotter than temperatures nearer the sun's surface - has puzzled scientists for decades. New observations made with instruments aboard Japan's Hinode satellite reveal the culprit to be nanoflares.

© Reale, et al. (2009)

|

This false-color temperature map shows solar active region AR10923, observed close to center of the sun's disk. Blue regions indicate plasma near 10 million degrees K.

"Why is the sun's corona so darned hot?" asks James Klimchuk, an astrophysicist with NASA. New observations made with instruments aboard Japan's Hinode satellite reveal the culprit to be nanoflares.

Nanoflares are small, sudden bursts of heat and energy. "They occur within tiny strands that are bundled together to form a magnetic tube called a coronal loop," says Klimchuk. Coronal loops are the fundamental building blocks of the thin, translucent gas known as the sun's corona.

Scientists previously thought steady heating explained the corona's million degree temperatures. However, observations showed that coronal loops have much higher density than the steady heating model predicts. Newer models based on nanoflares can explain the observed density. But no direct evidence of the nanoflares existed until now.

"Coronal loops are bundles of unresolved strands that are heated by storms of nanoflares."

Coronal heating is a dynamic process. The brightness of the observed X-ray and ultraviolet emission is strongly dependent on the density of the coronal plasma. Where there's low density, there isn't much brightness. Where there's high density, there's a lot of brightness. The corona is mostly bright at about 1 million degrees K.

Klimchuk and colleagues constructed a theoretical model to explain how plasma evolves within these coronal tubes and what causes temperatures to skyrocket. "We simulate a burst of heating and see how the corona responds," says Klimchuk. "Then we make predictions about how much emission we should see from plasma of different temperatures."

"What we see is 1 million degree K plasma that has received its energy from the heat flowing down from the superhot plasma," says Klimchuk. "For the first time, we have detected this 10 million degree plasma, which can only be produced by the impulsive energy bursts of nanoflares."

The Hinode observations and the scientists' analysis verify that nanoflares are occurring on the sun and that they explain much and perhaps most coronal heating. The observations also confirm "there is some nanoflare activity everywhere" in the sun's active regions, says Klimchuk.

Nanoflares influence satellites and radios

Nanoflares are responsible for changes in the X-ray and ultraviolet (UV) radiation that happen as an active region evolves. X-ray and UV get absorbed by Earth's upper atmosphere, which heats up and expands. Changes in the upper atmosphere can affect the orbits of satellites and space debris by slowing them down, an effect known as "drag." It is important to know the changing orbits so that maneuvers can be made to avoid space collisions. The X-ray and UV also affect the propagation of radio signals and thereby adversely affect communication and navigation systems.

The discovery that nanoflares play an important and perhaps dominant role in coronal heating paves the way to understanding how the sun affects Earth, our place in the universe.

Nanoflares are small, sudden bursts of heat and energy. "They occur within tiny strands that are bundled together to form a magnetic tube called a coronal loop," says Klimchuk. Coronal loops are the fundamental building blocks of the thin, translucent gas known as the sun's corona.

Scientists previously thought steady heating explained the corona's million degree temperatures. However, observations showed that coronal loops have much higher density than the steady heating model predicts. Newer models based on nanoflares can explain the observed density. But no direct evidence of the nanoflares existed until now.

"Coronal loops are bundles of unresolved strands that are heated by storms of nanoflares."

Coronal heating is a dynamic process. The brightness of the observed X-ray and ultraviolet emission is strongly dependent on the density of the coronal plasma. Where there's low density, there isn't much brightness. Where there's high density, there's a lot of brightness. The corona is mostly bright at about 1 million degrees K.

Klimchuk and colleagues constructed a theoretical model to explain how plasma evolves within these coronal tubes and what causes temperatures to skyrocket. "We simulate a burst of heating and see how the corona responds," says Klimchuk. "Then we make predictions about how much emission we should see from plasma of different temperatures."

"What we see is 1 million degree K plasma that has received its energy from the heat flowing down from the superhot plasma," says Klimchuk. "For the first time, we have detected this 10 million degree plasma, which can only be produced by the impulsive energy bursts of nanoflares."

The Hinode observations and the scientists' analysis verify that nanoflares are occurring on the sun and that they explain much and perhaps most coronal heating. The observations also confirm "there is some nanoflare activity everywhere" in the sun's active regions, says Klimchuk.

Nanoflares influence satellites and radios

Nanoflares are responsible for changes in the X-ray and ultraviolet (UV) radiation that happen as an active region evolves. X-ray and UV get absorbed by Earth's upper atmosphere, which heats up and expands. Changes in the upper atmosphere can affect the orbits of satellites and space debris by slowing them down, an effect known as "drag." It is important to know the changing orbits so that maneuvers can be made to avoid space collisions. The X-ray and UV also affect the propagation of radio signals and thereby adversely affect communication and navigation systems.

The discovery that nanoflares play an important and perhaps dominant role in coronal heating paves the way to understanding how the sun affects Earth, our place in the universe.