NASA's Hubble Space Telescope

Astronomers Uncover an Overheated Early Universe

© NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI) |

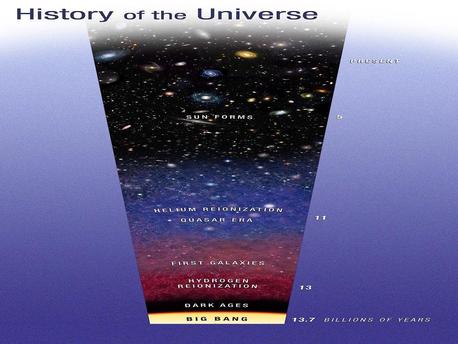

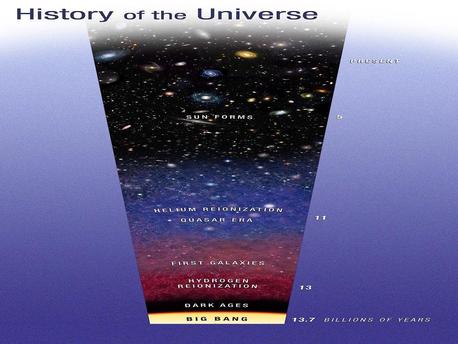

This diagram traces the evolution of the universe from the big bang to the present. Two watershed epochs are shown. Not long after the big bang, light from the first stars burned off a fog of cold hydrogen in a process called reionization. At a later epoch quasars, the black-hole-powered cores of active galaxies, pumped out enough ultraviolet light to reionize the primordial helium.

Using the newly installed Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) they have identified an era, from 11.7 to 11.3 billion years ago, when the universe stripped electrons off from primeval helium atoms — a process called ionization. This process heated intergalactic gas and inhibited it from gravitationally collapsing to form new generations of stars in some small galaxies. The lowest-mass galaxies were not even able to hold onto their gas, and it escaped back into intergalactic space.

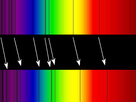

Michael Shull of the University of Colorado and his team were able to find the telltale helium spectral absorption lines in the ultraviolet light from a quasar — the brilliant core of an active galaxy. The quasar beacon shines light through intervening clouds of otherwise invisible gas, like a headlight shining through a fog. The beam allows for a core-sample probe of the clouds of gas interspersed between galaxies in the early universe.

The universe went through an initial heat wave over 13 billion years ago when energy from early massive stars ionized cold interstellar hydrogen from the big bang. This epoch is actually called reionization because the hydrogen nuclei were originally in an ionized state shortly after the big bang.

But Hubble found that it would take another 2 billion years before the universe produced sources of ultraviolet radiation with enough energy to do the heavy lifting and reionize the primordial helium that was also cooked up in the big bang.

This radiation didn't come from stars, but rather from quasars. In fact the epoch when the helium was being reionized corresponds to a transitory time in the universe's history when quasars were most abundant.

The universe was a rambunctious place back then. Galaxies frequently collided, and this engorged supermassive black holes in the cores of galaxies with infalling gas. The black holes furiously converted some of the gravitational energy of this mass to powerful far-ultraviolet radiation that would blaze out of galaxies. This heated the intergalactic helium from 18,000 degrees Fahrenheit to nearly 40,000 degrees. After the helium was reionized in the universe, intergalactic gas again cooled down and dwarf galaxies could resume normal assembly. "I imagine quite a few more dwarf galaxies may have formed if helium reionization had not taken place," said Shull.

So far Shull and his team only have one sightline to measure the helium transition, but the COS science team plans to use Hubble to look in other directions to see if the helium reionization uniformly took place across the universe.

The science team's results will be published in the October 20 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

Source: Hubblesite

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope

Astronomers Uncover an Overheated Early Universe

© NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI) |

This diagram traces the evolution of the universe from the big bang to the present. Two watershed epochs are shown. Not long after the big bang, light from the first stars burned off a fog of cold hydrogen in a process called reionization. At a later epoch quasars, the black-hole-powered cores of active galaxies, pumped out enough ultraviolet light to reionize the primordial helium.

Using the newly installed Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) they have identified an era, from 11.7 to 11.3 billion years ago, when the universe stripped electrons off from primeval helium atoms — a process called ionization. This process heated intergalactic gas and inhibited it from gravitationally collapsing to form new generations of stars in some small galaxies. The lowest-mass galaxies were not even able to hold onto their gas, and it escaped back into intergalactic space.

Michael Shull of the University of Colorado and his team were able to find the telltale helium spectral absorption lines in the ultraviolet light from a quasar — the brilliant core of an active galaxy. The quasar beacon shines light through intervening clouds of otherwise invisible gas, like a headlight shining through a fog. The beam allows for a core-sample probe of the clouds of gas interspersed between galaxies in the early universe.

The universe went through an initial heat wave over 13 billion years ago when energy from early massive stars ionized cold interstellar hydrogen from the big bang. This epoch is actually called reionization because the hydrogen nuclei were originally in an ionized state shortly after the big bang.

But Hubble found that it would take another 2 billion years before the universe produced sources of ultraviolet radiation with enough energy to do the heavy lifting and reionize the primordial helium that was also cooked up in the big bang.

This radiation didn't come from stars, but rather from quasars. In fact the epoch when the helium was being reionized corresponds to a transitory time in the universe's history when quasars were most abundant.

The universe was a rambunctious place back then. Galaxies frequently collided, and this engorged supermassive black holes in the cores of galaxies with infalling gas. The black holes furiously converted some of the gravitational energy of this mass to powerful far-ultraviolet radiation that would blaze out of galaxies. This heated the intergalactic helium from 18,000 degrees Fahrenheit to nearly 40,000 degrees. After the helium was reionized in the universe, intergalactic gas again cooled down and dwarf galaxies could resume normal assembly. "I imagine quite a few more dwarf galaxies may have formed if helium reionization had not taken place," said Shull.

So far Shull and his team only have one sightline to measure the helium transition, but the COS science team plans to use Hubble to look in other directions to see if the helium reionization uniformly took place across the universe.

The science team's results will be published in the October 20 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

Source: Hubblesite