NASA Telescope Finds

Elusive Buckyballs in Space for First Time

© NASA/JPL-Caltech |

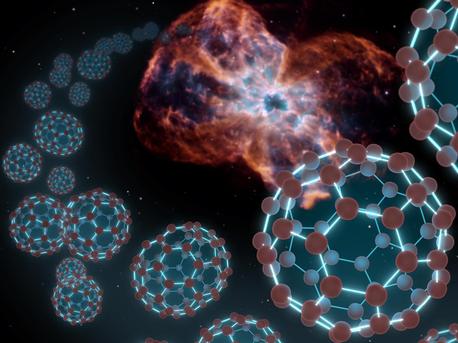

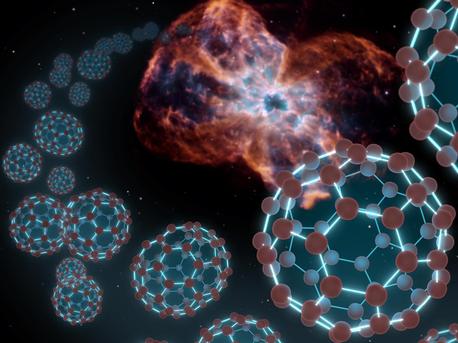

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope has at last found buckyballs in space, as illustrated by this artist's conception showing the carbon balls coming out from the type of object where they were discovered -- a dying star and the material it sheds, known as a planetary nebula. Buckyballs are made up of 60 carbon atoms organized into spherical structures that resemble soccer balls. They also look like Buckminister Fuller's architectural domes, hence their official name of buckministerfullerenes. The molecules were first concocted in a lab nearly 25 years ago, and were theorized at that time to be floating around carbon-rich stars in space. But it wasn't until now that Spitzer, using its sensitive infrared vision, was able to find convincing signs of buckyballs. The telescope found the molecules -- as well as their elongated, rugby-ball-like relatives, called C70 -- in the material around a dying star, or planetary nebula, called Tc 1. The star at the center of Tc 1 was once similar to our sun but as it aged, it sloughed off its outer layers, leaving only a dense white-dwarf star. Astronomers believe buckyballs were created in shed layers of carbon that blew off the star. Tc 1 does not show up that well in images, so a picture of the NGC 2440 nebula, taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, was used in this artist's conception.

"We found what are now the largest molecules known to exist in space," said astronomer Jan Cami of the University of Western Ontario, Canada, and the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif. "We are particularly excited because they have unique properties that make them important players for all sorts of physical and chemical processes going on in space." Cami has authored a paper about the discovery that will appear online Thursday in the journal Science.

Buckyballs are made of 60 carbon atoms arranged in three-dimensional, spherical structures. Their alternating patterns of hexagons and pentagons match a typical black-and-white soccer ball. The research team also found the more elongated relative of buckyballs, known as C70, for the first time in space. These molecules consist of 70 carbon atoms and are shaped more like an oval rugby ball. Both types of molecules belong to a class known officially as buckminsterfullerenes, or fullerenes.

The Cami team unexpectedly found the carbon balls in a planetary nebula named Tc 1. Planetary nebulas are the remains of stars, like the sun, that shed their outer layers of gas and dust as they age. A compact, hot star, or white dwarf, at the center of the nebula illuminates and heats these clouds of material that has been shed.

The buckyballs were found in these clouds, perhaps reflecting a short stage in the star's life, when it sloughs off a puff of material rich in carbon. The astronomers used Spitzer's spectroscopy instrument to analyze infrared light from the planetary nebula and see the spectral signatures of the buckyballs. These molecules are approximately room temperature -- the ideal temperature to give off distinct patterns of infrared light that Spitzer can detect. According to Cami, Spitzer looked at the right place at the right time. A century from now, the buckyballs might be too cool to be detected.

The data from Spitzer were compared with data from laboratory measurements of the same molecules and showed a perfect match.

"We did not plan for this discovery," Cami said. "But when we saw these whopping spectral signatures, we knew immediately that we were looking at one of the most sought-after molecules."

In 1970, Japanese professor Eiji Osawa predicted the existence of buckyballs, but they were not observed until lab experiments in 1985. Researchers simulated conditions in the atmospheres of aging, carbon-rich giant stars, in which chains of carbon had been detected. Surprisingly, these experiments resulted in the formation of large quantities of buckminsterfullerenes. The molecules have since been found on Earth in candle soot, layers of rock and meteorites.

The study of fullerenes and their relatives has grown into a busy field of research because of the molecules' unique strength and exceptional chemical and physical properties. Among the potential applications are armor, drug delivery and superconducting technologies.

Sir Harry Kroto, who shared the 1996 Nobel Prize in chemistry with Bob Curl and Rick Smalley for the discovery of buckyballs, said, "This most exciting breakthrough provides convincing evidence that the buckyball has, as I long suspected, existed since time immemorial in the dark recesses of our galaxy."

Previous searches for buckyballs in space, in particular around carbon-rich stars, proved unsuccessful. A promising case for their presence in the tenuous clouds between the stars was presented 15 years ago, using observations at optical wavelengths. That finding is awaiting confirmation from laboratory data. More recently, another Spitzer team reported evidence for buckyballs in a different type of object, but the spectral signatures they observed were partly contaminated by other chemical substances.

Source: NASA

NASA Telescope Finds

Elusive Buckyballs in Space for First Time

© NASA/JPL-Caltech |

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope has at last found buckyballs in space, as illustrated by this artist's conception showing the carbon balls coming out from the type of object where they were discovered -- a dying star and the material it sheds, known as a planetary nebula. Buckyballs are made up of 60 carbon atoms organized into spherical structures that resemble soccer balls. They also look like Buckminister Fuller's architectural domes, hence their official name of buckministerfullerenes. The molecules were first concocted in a lab nearly 25 years ago, and were theorized at that time to be floating around carbon-rich stars in space. But it wasn't until now that Spitzer, using its sensitive infrared vision, was able to find convincing signs of buckyballs. The telescope found the molecules -- as well as their elongated, rugby-ball-like relatives, called C70 -- in the material around a dying star, or planetary nebula, called Tc 1. The star at the center of Tc 1 was once similar to our sun but as it aged, it sloughed off its outer layers, leaving only a dense white-dwarf star. Astronomers believe buckyballs were created in shed layers of carbon that blew off the star. Tc 1 does not show up that well in images, so a picture of the NGC 2440 nebula, taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, was used in this artist's conception.

"We found what are now the largest molecules known to exist in space," said astronomer Jan Cami of the University of Western Ontario, Canada, and the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif. "We are particularly excited because they have unique properties that make them important players for all sorts of physical and chemical processes going on in space." Cami has authored a paper about the discovery that will appear online Thursday in the journal Science.

Buckyballs are made of 60 carbon atoms arranged in three-dimensional, spherical structures. Their alternating patterns of hexagons and pentagons match a typical black-and-white soccer ball. The research team also found the more elongated relative of buckyballs, known as C70, for the first time in space. These molecules consist of 70 carbon atoms and are shaped more like an oval rugby ball. Both types of molecules belong to a class known officially as buckminsterfullerenes, or fullerenes.

The Cami team unexpectedly found the carbon balls in a planetary nebula named Tc 1. Planetary nebulas are the remains of stars, like the sun, that shed their outer layers of gas and dust as they age. A compact, hot star, or white dwarf, at the center of the nebula illuminates and heats these clouds of material that has been shed.

The buckyballs were found in these clouds, perhaps reflecting a short stage in the star's life, when it sloughs off a puff of material rich in carbon. The astronomers used Spitzer's spectroscopy instrument to analyze infrared light from the planetary nebula and see the spectral signatures of the buckyballs. These molecules are approximately room temperature -- the ideal temperature to give off distinct patterns of infrared light that Spitzer can detect. According to Cami, Spitzer looked at the right place at the right time. A century from now, the buckyballs might be too cool to be detected.

The data from Spitzer were compared with data from laboratory measurements of the same molecules and showed a perfect match.

"We did not plan for this discovery," Cami said. "But when we saw these whopping spectral signatures, we knew immediately that we were looking at one of the most sought-after molecules."

In 1970, Japanese professor Eiji Osawa predicted the existence of buckyballs, but they were not observed until lab experiments in 1985. Researchers simulated conditions in the atmospheres of aging, carbon-rich giant stars, in which chains of carbon had been detected. Surprisingly, these experiments resulted in the formation of large quantities of buckminsterfullerenes. The molecules have since been found on Earth in candle soot, layers of rock and meteorites.

The study of fullerenes and their relatives has grown into a busy field of research because of the molecules' unique strength and exceptional chemical and physical properties. Among the potential applications are armor, drug delivery and superconducting technologies.

Sir Harry Kroto, who shared the 1996 Nobel Prize in chemistry with Bob Curl and Rick Smalley for the discovery of buckyballs, said, "This most exciting breakthrough provides convincing evidence that the buckyball has, as I long suspected, existed since time immemorial in the dark recesses of our galaxy."

Previous searches for buckyballs in space, in particular around carbon-rich stars, proved unsuccessful. A promising case for their presence in the tenuous clouds between the stars was presented 15 years ago, using observations at optical wavelengths. That finding is awaiting confirmation from laboratory data. More recently, another Spitzer team reported evidence for buckyballs in a different type of object, but the spectral signatures they observed were partly contaminated by other chemical substances.

Source: NASA