NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope

Pulverized Planet Dust May Lie Around Double Stars

© NASA/JPL-Caltech

|

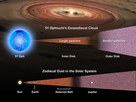

This artist's concept illustrates an imminent planetary collision around a pair of double stars. NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope found evidence that such collisions could be common around a certain type of tight double, or binary, star system, referred to as RS Canum Venaticorums or RS CVns for short. The stars are similar to the sun in age and mass, but they orbit tightly around each other. With time, they are thought to get closer and closer, until their gravitational influences change, throwing the orbits of planetary bodies circling around them out of whack. Astronomers say that these types of systems could theoretically host habitable planets, or planets that orbit at the right distance from the star pairs to have temperatures that allow liquid water to exist. If so, then these worlds might not be so lucky. They might ultimately be destroyed in collisions like the impending one illustrated here, in which the larger body has begun to crack under the tidal stresses caused by the gravity of the approaching smaller one. Spitzer's infrared vision spotted dusty evidence for such collisions around three tight star pairs. In this artist concept's, dust from ongoing planetary collisions is shown circling the stellar duo in a giant disk.

Drake is the principal investigator of the research, published in the Aug.19 issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The particular class of binary, or double, stars in the study are about as snug as stars get. Named RS Canum Venaticorums, or RS CVns for short, they are separated by only about two million miles (3.2 million kilometers), or two percent of the distance between Earth and our sun. The stellar pairs orbit around each other every few days, with one face on each star perpetually locked and pointed toward the other.

The close-knit stars are similar to the sun in size and are probably about a billion to a few billion years old -- roughly the age of our sun when life first evolved on Earth. But these stars spin much faster, and, as a result, have powerful magnetic fields, and giant, dark spots. The magnetic activity drives strong stellar winds -- gale-force versions of the solar wind -- that slow the stars down, pulling the twirling duos closer over time. And this is where the planetary chaos may begin.

As the stars cozy up to each other, their gravitational influences change, and this could cause disturbances to planetary bodies orbiting around both stars. Comets and any planets that may exist in the systems would start jostling about and banging into each other, sometimes in powerful collisions. This includes planets that could theoretically be circling in the double stars' habitable zone, a region where temperatures would allow liquid water to exist. Though no habitable planets have been discovered around any stars beyond our sun at this point in time, tight double-star systems are known to host planets; for example, one system not in the study, called HW Vir, has two gas-giant planets.

"These kinds of systems paint a picture of the late stages in the lives of planetary systems," said Marc Kuchner, a co-author from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "And it's a future that's messy and violent."

Spitzer spotted the infrared glow of hot dusty disks, about the temperature of molten lava, around three such tight binary systems. One of the systems was originally flagged as having a suspicious excess of infrared light in 1983 by the Infrared Astronomical Satellite. In addition, researchers using Spitzer recently found a warm disk of debris around another star that turned out to be a tight binary system.

The astronomy team says that dust normally would have dissipated and blown away from the stars by this mature stage in their lives. They conclude that something -- most likely planetary collisions -- must therefore be kicking up the fresh dust. In addition, because dusty disks have now been found around four, older binary systems, the scientists know that the observations are not a fluke. Something chaotic is very likely going on.

If any life forms did exist in these star systems, and they could look up at the sky, they would have quite a view. Marco Matranga, first author of the paper, from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and now a visiting astronomer at the Palermo Astronomical Observatory in Sicily, said, "The skies there would have two huge suns, like the ones above the planet Tatooine in 'Star Wars.'"

Source: NASA

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope

Pulverized Planet Dust May Lie Around Double Stars

© NASA/JPL-Caltech

|

This artist's concept illustrates an imminent planetary collision around a pair of double stars. NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope found evidence that such collisions could be common around a certain type of tight double, or binary, star system, referred to as RS Canum Venaticorums or RS CVns for short. The stars are similar to the sun in age and mass, but they orbit tightly around each other. With time, they are thought to get closer and closer, until their gravitational influences change, throwing the orbits of planetary bodies circling around them out of whack. Astronomers say that these types of systems could theoretically host habitable planets, or planets that orbit at the right distance from the star pairs to have temperatures that allow liquid water to exist. If so, then these worlds might not be so lucky. They might ultimately be destroyed in collisions like the impending one illustrated here, in which the larger body has begun to crack under the tidal stresses caused by the gravity of the approaching smaller one. Spitzer's infrared vision spotted dusty evidence for such collisions around three tight star pairs. In this artist concept's, dust from ongoing planetary collisions is shown circling the stellar duo in a giant disk.

Drake is the principal investigator of the research, published in the Aug.19 issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The particular class of binary, or double, stars in the study are about as snug as stars get. Named RS Canum Venaticorums, or RS CVns for short, they are separated by only about two million miles (3.2 million kilometers), or two percent of the distance between Earth and our sun. The stellar pairs orbit around each other every few days, with one face on each star perpetually locked and pointed toward the other.

The close-knit stars are similar to the sun in size and are probably about a billion to a few billion years old -- roughly the age of our sun when life first evolved on Earth. But these stars spin much faster, and, as a result, have powerful magnetic fields, and giant, dark spots. The magnetic activity drives strong stellar winds -- gale-force versions of the solar wind -- that slow the stars down, pulling the twirling duos closer over time. And this is where the planetary chaos may begin.

As the stars cozy up to each other, their gravitational influences change, and this could cause disturbances to planetary bodies orbiting around both stars. Comets and any planets that may exist in the systems would start jostling about and banging into each other, sometimes in powerful collisions. This includes planets that could theoretically be circling in the double stars' habitable zone, a region where temperatures would allow liquid water to exist. Though no habitable planets have been discovered around any stars beyond our sun at this point in time, tight double-star systems are known to host planets; for example, one system not in the study, called HW Vir, has two gas-giant planets.

"These kinds of systems paint a picture of the late stages in the lives of planetary systems," said Marc Kuchner, a co-author from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "And it's a future that's messy and violent."

Spitzer spotted the infrared glow of hot dusty disks, about the temperature of molten lava, around three such tight binary systems. One of the systems was originally flagged as having a suspicious excess of infrared light in 1983 by the Infrared Astronomical Satellite. In addition, researchers using Spitzer recently found a warm disk of debris around another star that turned out to be a tight binary system.

The astronomy team says that dust normally would have dissipated and blown away from the stars by this mature stage in their lives. They conclude that something -- most likely planetary collisions -- must therefore be kicking up the fresh dust. In addition, because dusty disks have now been found around four, older binary systems, the scientists know that the observations are not a fluke. Something chaotic is very likely going on.

If any life forms did exist in these star systems, and they could look up at the sky, they would have quite a view. Marco Matranga, first author of the paper, from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and now a visiting astronomer at the Palermo Astronomical Observatory in Sicily, said, "The skies there would have two huge suns, like the ones above the planet Tatooine in 'Star Wars.'"

Source: NASA